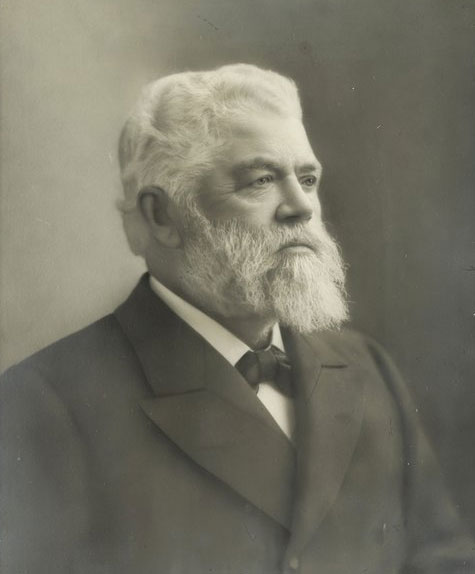

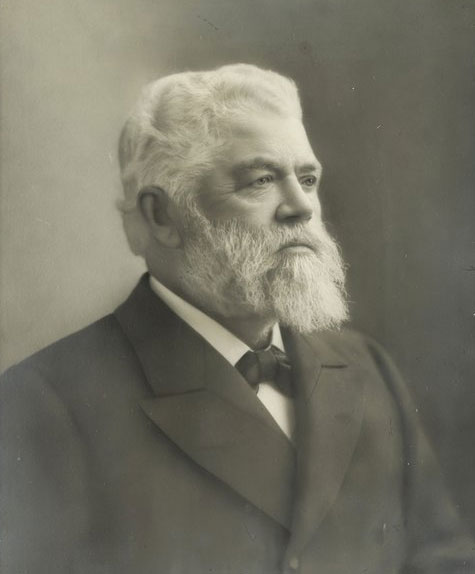

George Elias Tuckett

1835 - 1900

In 1842 Elias and Mary Tuckett immigrated with their daughter and two sons to Hamilton, Upper Canada, where Elias found work as a tallow

chandler. Although in later life George Elias Tuckett regretted his lack of formal instruction, he had, by the standards of his class, a

sound education ‐ for a short time he attended a local private academy. Tuckett's early employment remains unknown; he may have

apprenticed as a shoemaker. In 1852, at the age of 17, he opened a shoe store in Hamilton but his business quickly failed. During the

fifties and early sixties, he entered three partnerships with Hamilton tobacconists to make tobacco products. His associates probably

supplied the capital and did the marketing while Tuckett engaged in manufacturing or supervised others in the work.

In 1842 Elias and Mary Tuckett immigrated with their daughter and two sons to Hamilton, Upper Canada, where Elias found work as a tallow

chandler. Although in later life George Elias Tuckett regretted his lack of formal instruction, he had, by the standards of his class, a

sound education ‐ for a short time he attended a local private academy. Tuckett's early employment remains unknown; he may have

apprenticed as a shoemaker. In 1852, at the age of 17, he opened a shoe store in Hamilton but his business quickly failed. During the

fifties and early sixties, he entered three partnerships with Hamilton tobacconists to make tobacco products. His associates probably

supplied the capital and did the marketing while Tuckett engaged in manufacturing or supervised others in the work.

A short‐lived partnership with David Rose followed his shoe‐store venture. Tuckett's health failed and he quit to work on a

lake boat for several years. He returned to Hamilton to go into partnership with Amos Hill. In 1857 he struck out on his own again, hiring

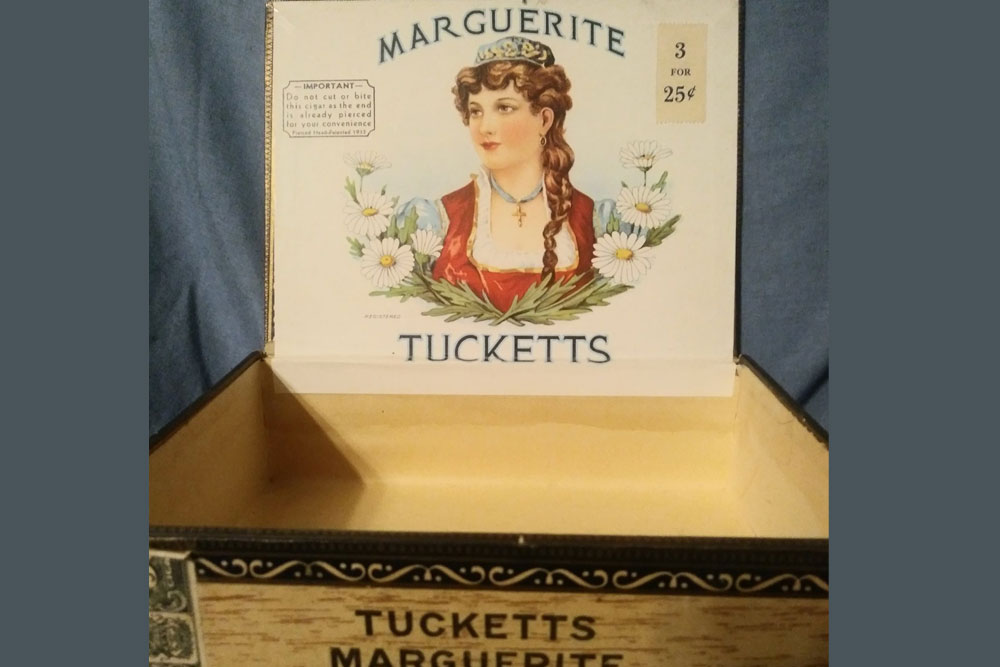

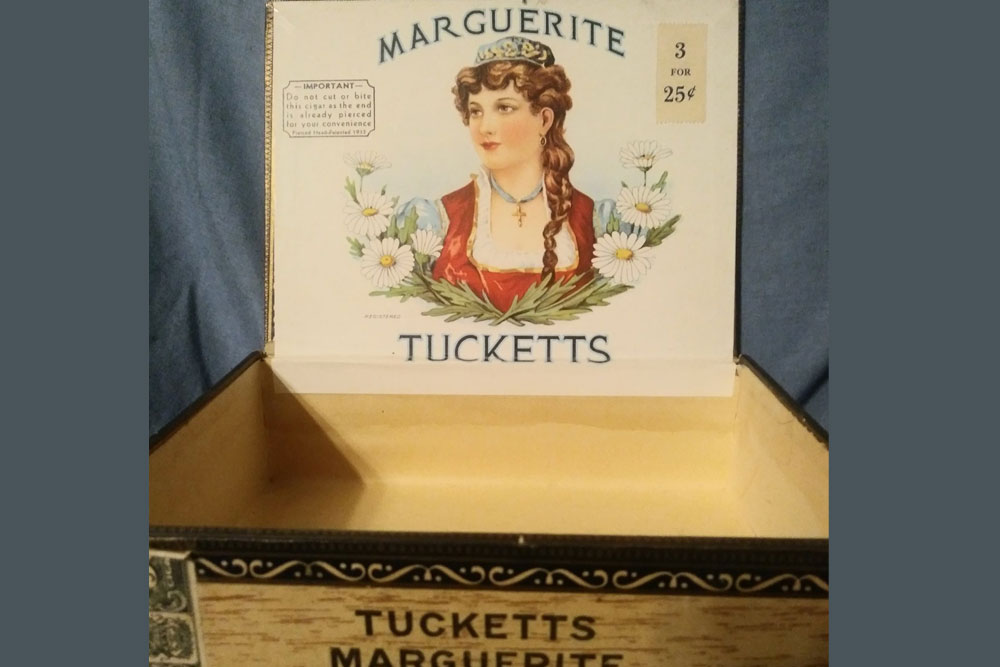

three or four men to make cigars. To retail his product, he opened a store in London. When he married, probably the following year. his

wife also contributed to the business by selling cigars in the market and at fairs in Hamilton.

In 1862 Tuckett gave up cigar making to manufacture plug tobacco in partnership with Alfred Campbell Quimby, a Hamilton tobacconist. The

American Civil War disrupted tobacco exports to Canada and protected the new industry. Quimby and Tuckett are reported to have gone behind

Confederate lines to purchase Virginia tobacco, which could then be shipped north as Canadian property. The stress of

George Elias Tuckett

1835 - 1900

such transactions

affected Tuckett's health and in early 1864 the business was dissolved.

The following year Tuckett and John Billings purchased the interest of Nathan B. Gatchell in the Hamilton Glass Works and took in three

partners. Difficulties in marketing the glassware quickly disillusioned Tuckett and, after just one year, he decided to return to the

manufacture of plug tobacco, this time with Billings. Their business prospered. By 1868 Tuckett and Billings employed 70 hands, more than

either of the other two tobacco manufacturers in Hamilton. Three years later they doubled their plant's capacity. In 1875 the credit

reporter of R. G. Dun and Company judged the partners to be good risks. The value of their assets, including their factory, which had cost

them $6,000 in 1866, was placed at $60,000 to $75,000. Tuckett possessed real estate outside the business worth $40,000 to $50,000, including

a residence worth $16,000.

either of the other two tobacco manufacturers in Hamilton. Three years later they doubled their plant's capacity. In 1875 the credit

reporter of R. G. Dun and Company judged the partners to be good risks. The value of their assets, including their factory, which had cost

them $6,000 in 1866, was placed at $60,000 to $75,000. Tuckett possessed real estate outside the business worth $40,000 to $50,000, including

a residence worth $16,000.

The partnership lasted until Billings retired in 1880. Tuckett's elder son, George Thomas, and his nephew, John Elias Tuckett, then became

partners in George E. Tuckett and Son. The nephew had for some time attended to the company's branch in Danville, Va. In the late 1880s

George Elias began reducing his active involvement in the firm and with incorporation in 1892 the day‐to‐day operations became

fully his son's responsibility.

With some success, Tuckett had been using paternalistic labour policies to promote loyalty among the approximately 400 workers in his employ

by the 1880s. His voluntary introduction in 1882 of the nine hour day as well as profit sharing and bonuses brought him their goodwill and

much favourable publicity. At the same time different terms of employment segmented the labour force, thereby enhancing his control of the

work process. The terms conformed to separate stages in the production process. Tuckett believed that piece-rates for the most skilled

workers, the rollers and plug makers, best sustained and increased production. If they wanted to earn the same or more income than other

workers in the factory at large, they had to speed up their production. Their dependence on piece rates made them the drivers of those paid

daily rates.

The publicity arising from his success and his system of factory labour made Tuckett an attractive candidate for public office. His political

innocence, however, rendered his political career mercurial. He

considered himself a social radical and, as befitted a successful artisan,

he believed in charting an independent political course. Originally a reformer, he was drawn to the Conservative party by the National Policy. Anticipating a federal election, local Conservatives prevailedupon Tuckett in 1895 to accept the nomination for one of the Hamilton

seats. The Liberals feared his electoral appeal and offered to support him for mayor in 1896 ‐ he had been an alderman in 1863, 1864, and

1884 ‐ if he declined to stand for the federal election, and he agreed.

Tuckett ran on a municipal platform of good government and low taxes. He was, however, a target for Hamilton's moral reform movement. He

manufactured tobacco; he was accused of being a patron of saloons; as a director of the Hamilton Jockey Club, he abetted gambling; as a

shareholder in the Hamilton Street Railway and a recipient of tax and water-rate exemptions for his factory, he benefited from the very

municipal expenditures he claimed were too high. The last was the most serious charge: his $85,000 exemption on an assessed value of

$129,000 cost the city $1,700 a year in revenue. Yet Tuckett won the election by a landslide. He had nevertheless alienated the Conservative

party and, with no commitment from the Liberals to support him for mayor in 1897, his re-election bid collapsed. He lost decisively.

When he died in 1900, George Elias Tuckett was a socially prominent and very wealthy man. He was an Anglican and generous to his own

congregation, a freemason, and president of the St George's Society (1898). Besides considerable real estate, he had accumulated

personal property worth $708,705, including nearly $375,000 in bank and other shares. At various times he had served on the boards of

directors of the Bank of British North America, the Traders Bank of Canada, and the Hamilton and Barton Incline Railway Company, and

he had been president of the Hamilton Steamboat Company. He also had invested in the Hamilton Street Railway and the Hamilton Steel and

Iron Company. Though he may not have received an extensive education, Tuckett possessed an aptitude for adapting factory organization more

efficiently to mass production and a willingness to experiment with labour relations. To these qualities, his success might be attributed.

personal property worth $708,705, including nearly $375,000 in bank and other shares. At various times he had served on the boards of

directors of the Bank of British North America, the Traders Bank of Canada, and the Hamilton and Barton Incline Railway Company, and

he had been president of the Hamilton Steamboat Company. He also had invested in the Hamilton Street Railway and the Hamilton Steel and

Iron Company. Though he may not have received an extensive education, Tuckett possessed an aptitude for adapting factory organization more

efficiently to mass production and a willingness to experiment with labour relations. To these qualities, his success might be attributed.